The 2023 Stanford AI in Fintech Forum

The Stanford Fintech in AI Forum organized by Stanford Prof. Kay Giesecke provides an invaluable opportunity for quantitative ML professionals in finance to gather and exchange insights. I’ll attempt to cover the presentations and takeaways in the agenda:

https://fintech.stanford.edu/events/conferences/ai-fintech-forum-2023

Monetary Tightening and U.S. Bank Fragility in 2023: Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs? Amit Seru (Stanford GSB)

Intimate Partner Financial Abuse* Jessica Staddon (JP Morgan AI Research)

Why is Intermediating Houses so Difficult? Evidence from iBuyers Greg Buchak (Stanford)

Multimodal Machine Learning in Finance Sanjiv Das (Santa Clara University and Amazon)

Leveraging AI in Fixed Income Tejash Shah (Bloomberg)

Panel: Reinforcement Learning in Financial Services/Markets

- Ashwin Rao (Stanford)

- Ian Osband (Google DeepMind)

- Svitlana Vyetrenko (JP Morgan)

Panel: Generative AI in Financial Services/Markets

- James Cham (Bloomberg Beta)

- Sanjiv Das (Santa Clara University and Amazon)

- Leonard Tam (Amicus.ai)

Amit presented topics related to his working paper https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31048/w31048.pdf. He delved into the issues surrounding bank failures and the risks associated with the banking system. Generally, an investment fund example explains the inherent instability of banks, where investors are promised a risk-free investment yet the bank invests in risky assets, i.e. behaving like an investment fund but promising something else. This leads to the phenomenon of bank runs, where depositors rush to withdraw their money out of fear that the bank might renege, causing instability.

Amit’s paper explicates the role of increased interest rates on the banking sector. Amit explains that banks usually fund themselves from deposits promising a low interest rate, investing these funds into long-term securities or loans that provide higher returns. However due to the Federal Reserve’s recent increase in interest rates, the value of these long-term securities has declined, causing some banks to struggle.

Amit uses the example of Silicon Valley Bank, which saw a massive influx of deposits, primarily in long-term securities. When interest rates rose, the value of these securities fell, but the bank wasn’t initially concerned because it didn’t need to sell these securities unless depositors demanded their money back. However, when Silicon Valley’s startup clients needed to draw on their cash due to a slowdown in the economy, the bank was forced to liquidate some of these devalued securities, leading to a loss.

This incident sparked awareness about the sensitivity of bank investments to interest rates, creating uncertainty and leading to a run on deposits at Silicon Valley Bank. Amit stresses that the key issue here is whether depositors are actively paying attention to the health of the bank and willing to withdraw their funds quickly. The issue becomes more critical when a large proportion of deposits are uninsured and therefore more likely to be withdrawn swiftly in case of any perceived risk.

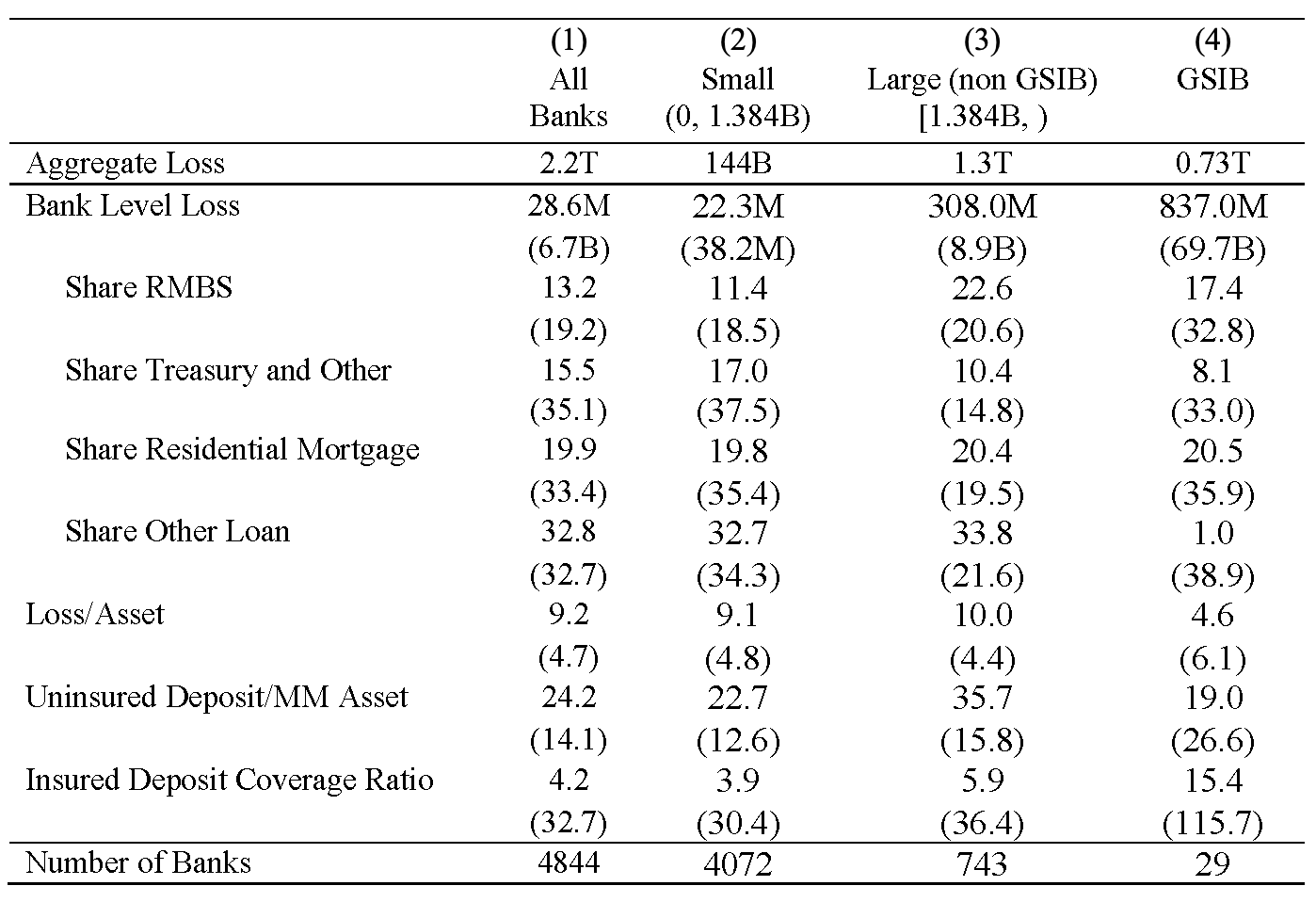

Amit’s paper analyzes the potential impact of recent increases in interest rates on the financial stability of US banks. This study reveals that the marked-to-market value of bank assets is $2 trillion less than their book value, resulting in an average decrease of 10% across all banks. The worst-hit banks (in the bottom 5th percentile) experienced a 20% drop.

The paper highlights that uninsured leverage (Uninsured Debt/Assets) is a crucial factor in determining whether the decreased asset values could lead to insolvency. This is because uninsured depositors, unlike insured ones, risk losing a portion of their deposits if a bank fails, providing them an incentive to withdraw their money.

Using the recent failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) as a case study, the authors demonstrate that SVB wasn’t the worst-capitalized bank but had a disproportionately high level of uninsured funding. They also found that 10% of banks have larger unrecognized losses and lower capitalization than SVB.

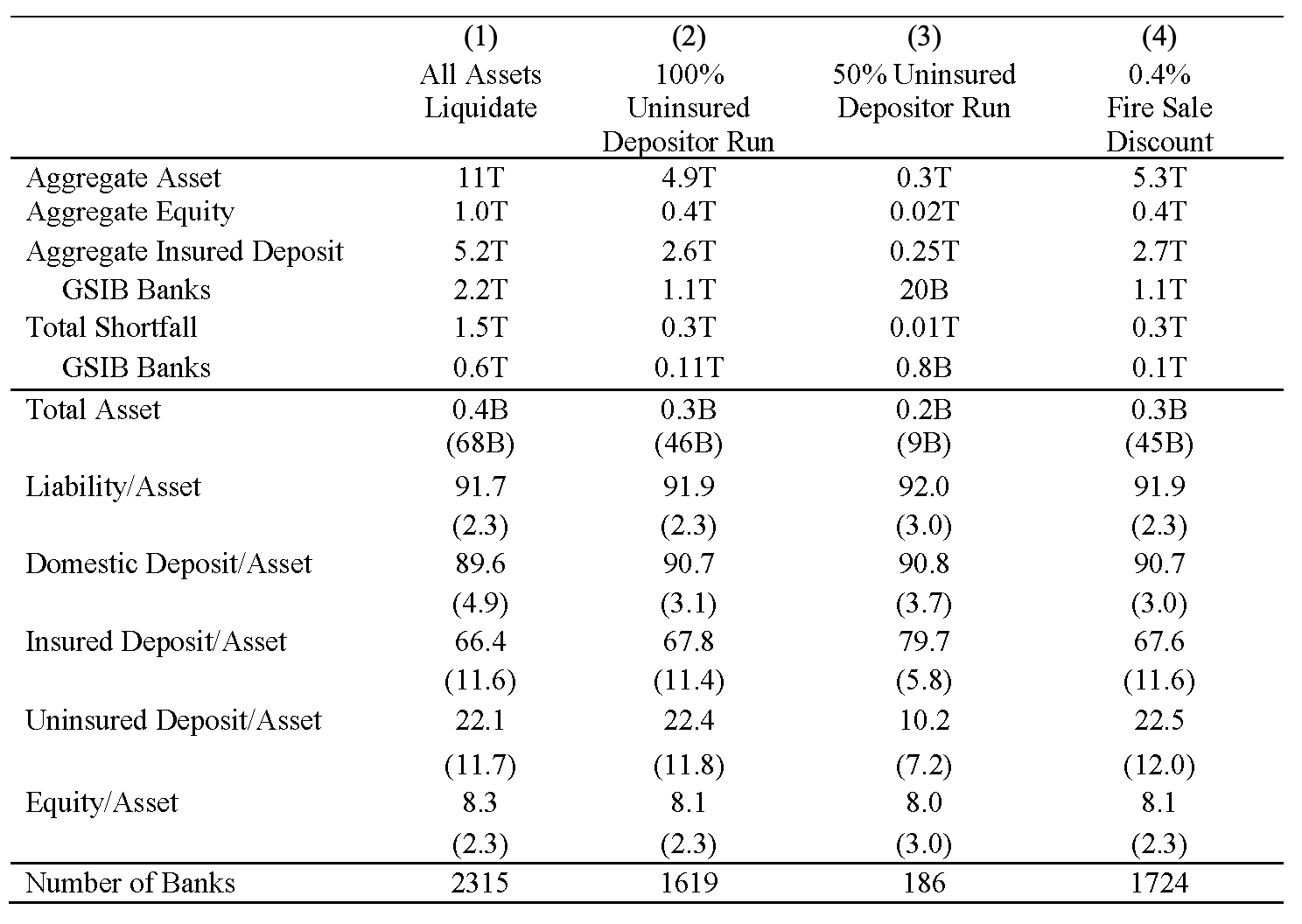

They calculated similar incentives for the entire sample of US banks and found that if only half of uninsured depositors withdraw their money, almost 190 banks could potentially risk impairing insured depositors, with an estimated $300 Bn of insured deposits at risk. If such withdrawals trigger even small asset fire sales, many more banks could be at risk.

Amit further suggests that stress tests, designed after the 2007-2008 financial crisis to assess the resilience of banks in crisis situations, might have overlooked the risk of rising interest rates in combination with correlated deposits. He believes that regulators should not only focus on past crises but also anticipate the types of risk that could arise in changing economic environments. He also emphasizes the need for banks to maintain a sufficient amount of equity to absorb potential losses, essentially allowing them to internalize the risks they take.

It may be the reasons for the existence of banks despite their unstable nature are largely historical, with trust being a significant factor in their development. The promise of risk-free investment holds a disciplining effect on the bank as it makes them careful with their investments.

There are two solutions to creating a bank that is impervious to bank runs. The first solution is to match the riskless nature of deposits with equally riskless investments, sometimes referred to as narrow banking. The second solution involves allowing depositors to withdraw their money at the current value of the bank, similar to how a mutual fund operates.

Government insurance, such as FDIC insurance, guarantees a certain amount to the depositor, creating a system where if the bank fails, the government pays out, and if the bank profits, equity holders keep the profits. In some ways, the modern banking system persists because it is heavily subsidized by government guarantees. Other forms of investments such as corporate bonds, equity contracts, and mutual funds could potentially serve the same function without risking the entire economy. The banking system, as it currently exists, might not be the most efficient model for modern economic systems.

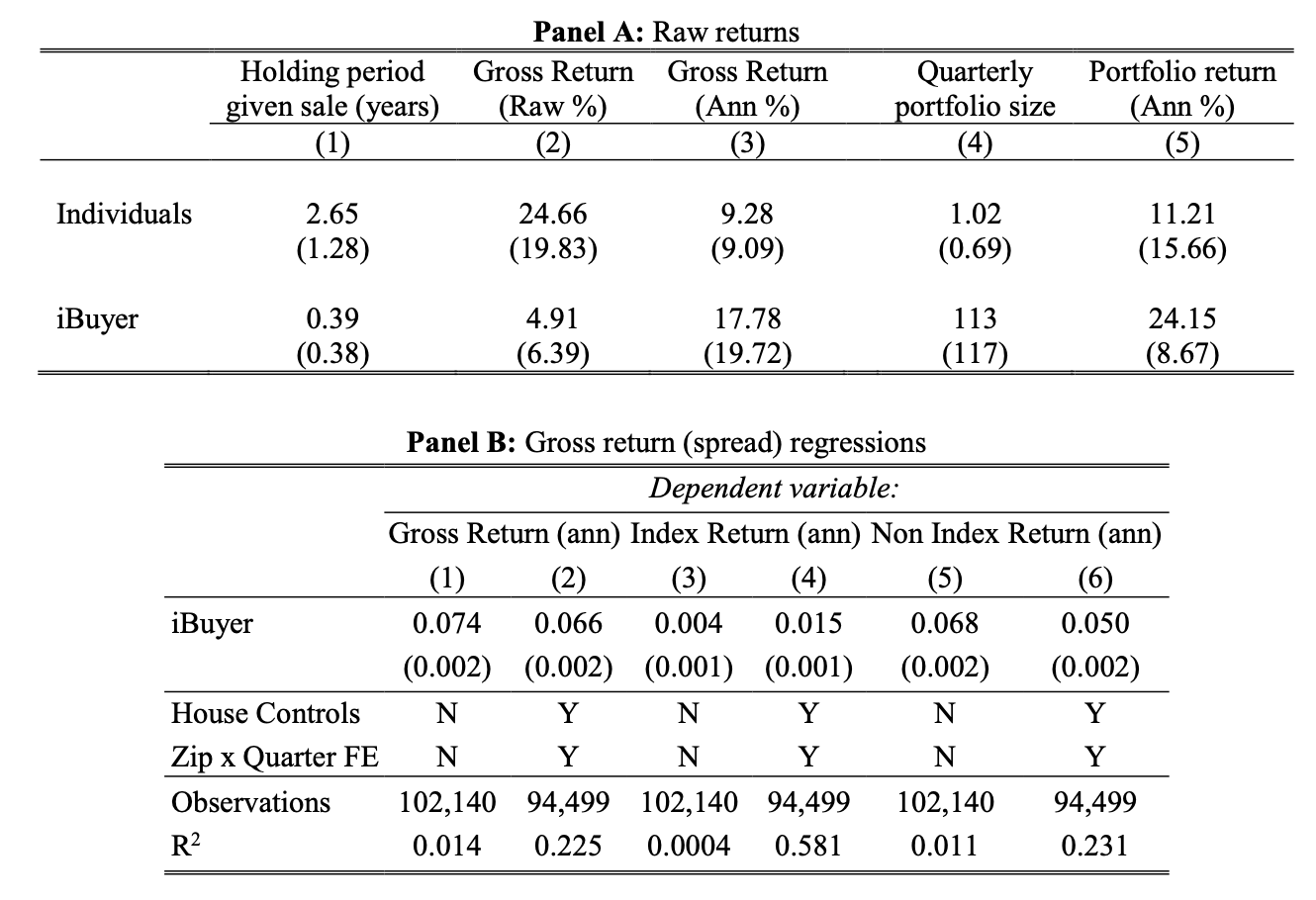

Greg Buchak discussed his paper “Why is Intermediating Houses so Difficult? Evidence from iBuyers”. The paper explores the complexities and challenges of dealer-intermediation in the residential real estate market, specifically focusing on “iBuyers” — tech-based platforms that rapidly buy and sell homes. These iBuyers provide liquidity to homeowners by facilitating swift sales, thereby avoiding the typically drawn-out sales process. They earn a 5% spread on transactions, and their pricing is primarily driven by algorithmic models.

However, the study points out that iBuyers tend to operate in markets where homes can be easily valued by automated models and where the market itself is already liquid. This suggests a potential drawback: the speed of their operations may lead to a loss of information about house attributes that are hard to capture algorithmically, which can result in adverse selection.

To further understand this, the authors created a dynamic structural search model with adverse selection. The model showed that to provide valuable liquidity services, transactions need to be completed quickly. However, quick transactions can make it harder to price homes accurately, leading to adverse selection. The analysis shows that low underlying liquidity in a market can exacerbate this problem.

The study suggests that iBuyers’ technology strikes a balance by allowing them to transact quickly while minimizing information loss. Yet, even with this technology, intermediation is profitable only for the most liquid and easy-to-value houses. Therefore, iBuyers can provide liquidity, but this service is most valuable in markets where liquidity is already relatively high. The paper also points to a limited scope for iBuyers to expand their operations beyond these markets.

Greg’s talk had a balanced analysis of the new business strategy pursued by companies such as Zillow.

Sanjiv discussed topics in multimodal data - not the typical vision and text we usually encounter in AI, but rather tabular and time series data. He traversed a broad swath of papers including but not limited to: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S104244312200107X, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378426621001515, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405918821000040, and https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.03285.

The first paper investigates the impact of globalization on systemic risk in emerging markets. The study expands the existing research, predominantly focused on developed countries, to include emerging markets. The authors analyze systemic risk among 1048 financial institutions in 23 emerging markets, divided into 5 regions, along with 369 U.S. financial institutions. Using a systemic risk score that combines banking system interconnectedness with default probabilities, the study finds that systemic risk in emerging markets varies across regions and is largely dependent on the banking system’s interconnectedness within each region.

The second paper introduces a dynamic programming methodology designed to optimize investor outcomes over multiple competing goals, even under limited financial resources. This method departs from the commonly used Monte Carlo approach by leveraging investor preferences to dynamically determine optimal choices regarding goal fulfillment and investment portfolio selection. The approach is computationally efficient and adaptable to numerous investor goals spread over different or concurrent time periods. The probabilities of attaining each goal under the optimal scenario are also calculated to align with the investor’s preferences.

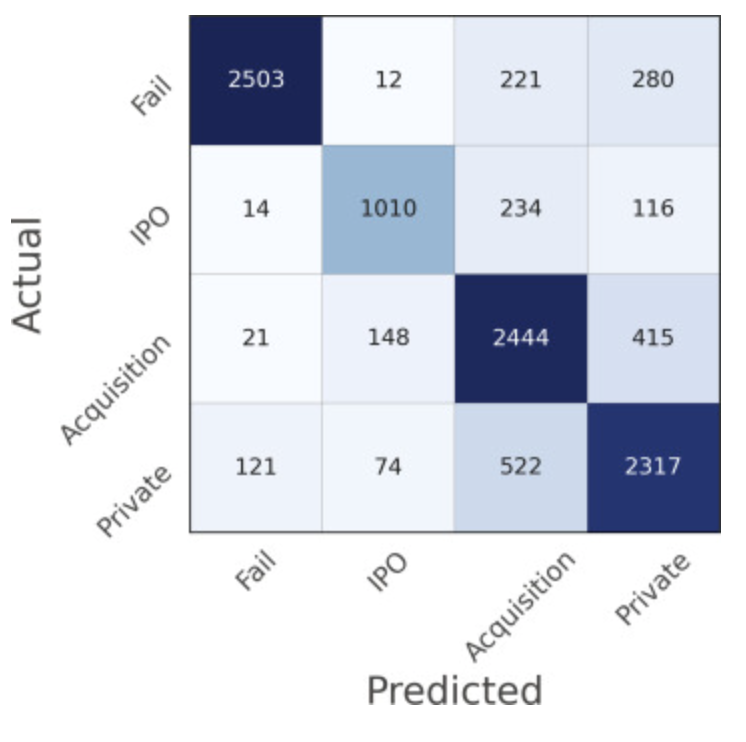

The third paper develops a machine-learning model, CapitalVX, to predict the outcomes for startups using a large dataset of venture capital financing and related startup firms from CrunchBase. The model successfully predicts startup outcomes and follow-on funding with an accuracy of 80–89%. This research implies that venture capital/private equity firms could potentially leverage machine learning to screen potential investments using publicly available information, thereby freeing up resources for mentoring and monitoring their investments.

The fourth paper presents Amazon SageMaker Clarify, a feature of Amazon SageMaker that provides insights into data and machine learning models by identifying biases and explaining predictions. Launched in December 2020, Clarify supports bias detection and feature importance computation across the machine learning lifecycle, from data preparation to model evaluation and post-deployment monitoring. The paper discusses customer use cases, deployment results, customer feedback, and quantitative evaluations. It concludes with lessons learned and best practices for implementing fairness and explanation tools in practice.

Sanjiv suggested ML could improve venture investing

Sanjiv suggested ML could improve venture investing

The afternoon presentations took on a lighter basis. Jash from Bloomberg gave a working tour of the gee-whiz functionality of the Bloomberg terminal, for instance demonstrating natural language queries for retrieval of various bond details.

The panel Reinforcement Learning in Financial Services/Markets had the excellent researchers Ian from Google Deepmind and Svitlana from JP Morgan. Svitlana had anecdotes on optimizing simulator environments for RL while agreeing with Ian that sometimes the constant inputs to the simulator, such as volatility, could be arbitrary. After the panel, I picked Ian’s brain regarding GPT-4 training recipes. He was optimistic on the alignment RL methods being the correct path to further performance while I remained more skeptical on the pace of development.

Lastly, my panel with Sanjiv expertly fused an academic and product view, with Bloomberg Beta partner James Cham adeptly translating some of our more technical points into plain English. One prevalent concern was whether genAI tools will disrupt work and take people jobs. My view is that it’ll uplevel many types of workers to be 10x productive.

In appreciation of the organizer Kay, I should describe his work on loan portfolio engines currently being commercialized at Infima. His group’s work from 2020 https://arxiv.org/abs/1607.02470 describes a deep learning model to analyze multi-period mortgage risk using an extensive dataset of over 120 million mortgages across the US from 1995 to 2014. The model’s estimators take into account loan-specific and macroeconomic variables to a zip-code level to determine the structures of conditional probabilities of prepayment, foreclosure, and various states of delinquency.

Key findings highlight the highly nonlinear relationship between these variables and borrower behavior, especially prepayment. The study underscores the impact of local economic conditions, with state unemployment showing the greatest explanatory power, indicating a close relationship between housing finance markets and the macroeconomy. Prepayment events are found to be highly sensitive to various factors in a nonlinear way, and this sensitivity is dependent on several variables. As expected, the effect of unemployment rates on prepayment is highly dependent on the borrower’s credit score. Higher credit score borrowers are estimated to prepay at significantly higher rates than those with lower scores in all unemployment scenarios. However, with rising unemployment, the prepayment rate of low credit score borrowers decreases significantly.

The study also finds nontrivial interactions between unemployment and other variables, such as loan-to-value ratios, mortgage rates, and house price appreciation, affecting both prepayment and credit risks. Interestingly, the delinquency rate drops more in response to house price appreciation when unemployment is high compared to when it’s low. This suggests that sufficient home equity can insulate borrowers from labor market shocks. Overall, the results have significant implications for mortgage-backed security investors, rating agencies, and housing finance policymakers.

After all the brain flexing, the speakers had a celebration nearby Stanford campus at a northern Italian restaurant. A fitting end to a day of high finance!

*Note: I missed Jessica’s presentation due to work obligations.