Compressive Sensing vs Deep Learning

“In a way, residency is training the neural network of physicians”

-- Stanford Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology Robert Chang

Recent trends in computational image analysis include compressive sensing (a topic of my thesis) and extremely popular deep learning (DL) approaches. The discussion here targets the “unreasonable effectiveness” (Yann LeCun at GTC) of deep neural networks (DNN) in practical, physician-centric approachs. A brief introduction is given to compressive sensing (CS), parallels are drawn between CS and DL, and a commentary with figures on why CS has not seen more uptake in image analysis as opposed to DL where application has been impressive, for instance Ben Graham’s winning DL algorithm). The discussion focusses on human sensitivity to texture that DNNs identify in a familiar fashion to physicians.

Compressive sensing overview

CS has an extremely robust theoretical foundation (arguably in contrast to DL) built on foundational work from Emmanuel Candes (Google Scholar), Terence Tao (2006 Fields Medalist, blog), and David Donoho (Stanford Statistics). In short, it’s a method to exceed Nyquist sampling limits given prior information on the sparsity of the signal. There are three requirements for CS:

- The signal is sparse in a transform domain.

- The signal is sampled incoherently in the transform domain.

- The signal is reconstructed using convex optimization with a sparsity promoting L1 norm reconstruction.

The first point broadens the scope of the technique greatly. If your signal is not sparse in it’s natural habitat, that’s fine. Just transform it to a domain where it is sparse, e.g. an NMR signal is sampled in the frequency (re: Fourier) domain and transformed to the wavelet space where biological images are sparse (sparsity in MR images). The second point and the third point are related. The signal is sampled incoherently in the transform domain such that aliasing propagates as noise, which is then iteratively filtered using convex optimization,

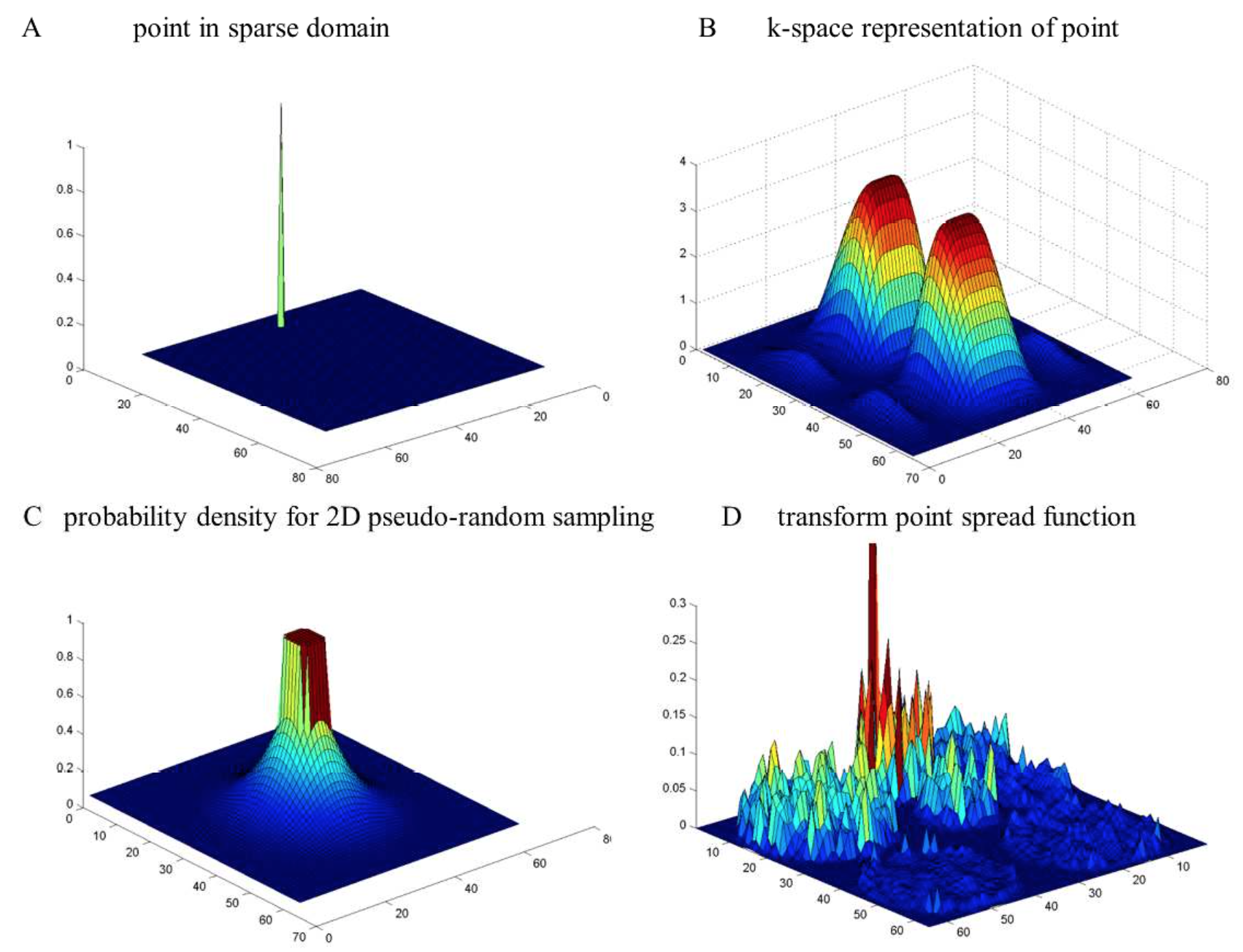

A signal in the wavelet domain (A) is transformed to the frequency domain (B). When is it is sampled by the probability density function in (C), the signal in the sparse domain has a noise-like background. The background can be filtered to recover the signal.

A signal in the wavelet domain (A) is transformed to the frequency domain (B). When is it is sampled by the probability density function in (C), the signal in the sparse domain has a noise-like background. The background can be filtered to recover the signal.

Exact recovery of the signal is given based on the signal sparsity and the sampling method (in section “Optimizing the sampling method” from my paper and citations in that section).

Unfortunately, though the CS signal reconstruction is convergent as measured by image error, many physicians find wavelet-based CS images as “artificial”. Namely, they lack noise-like texture that physicians perceive as features (an example in Fig. 3). Moreover, post-injection of noise to generate familiar image characteristics is inherently undesirable and “artificial”.

Medical Features from a CNN

Working with Prof. Chang on automatic diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy, he noted “In a way, residency is training the neural network of physicians.” Our algorithm (15th on Kaggle) used many of the techniques featured in other blog posts on the topic: common-sense data augmentation, training a deep convolutional NN on 1024x1024 images, both-eyes analysis, etc. etc. (Unfortunately, we didn’t do model ensembling due to time constraints, widely known as beneficial).

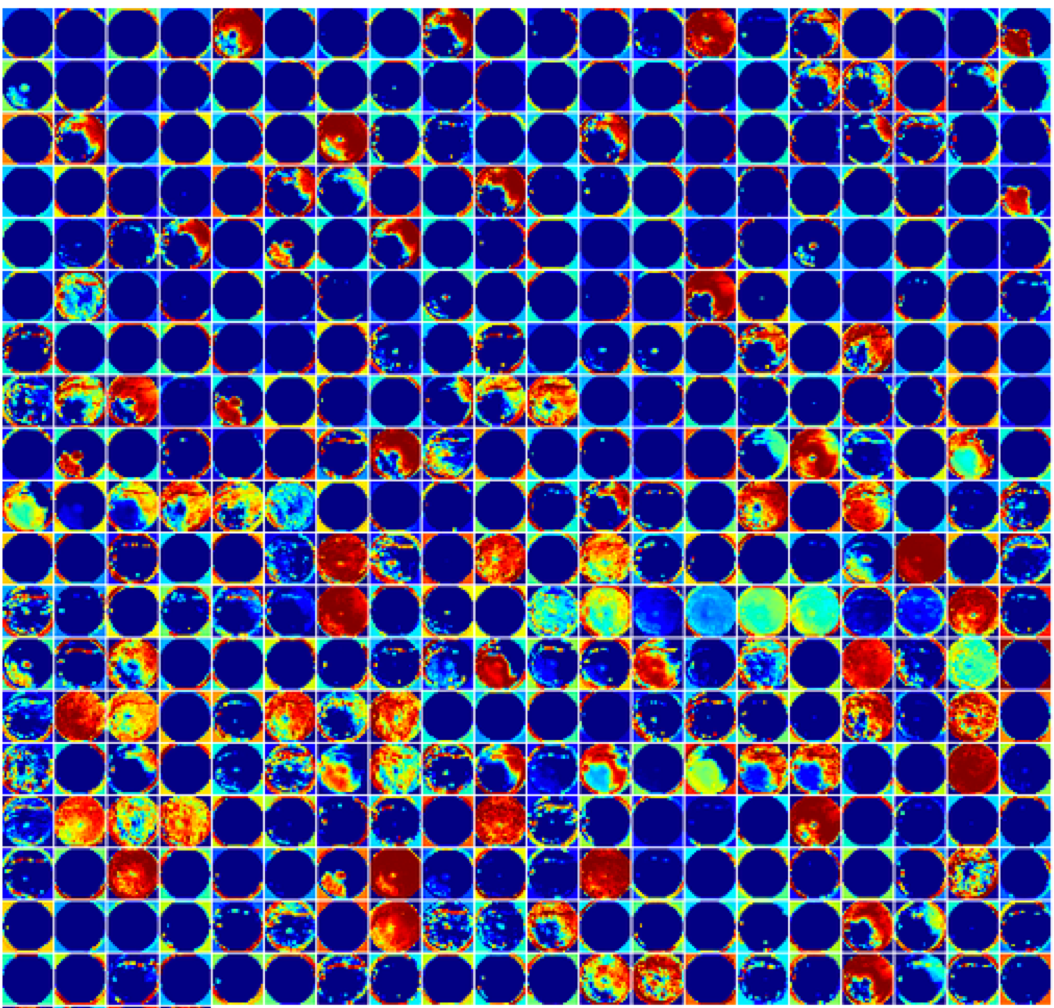

It’s possible to visualize the features extracted by the CNN and below is shown the features for a pooling layer trained on 40000+ retinal images using DIGITS 2 (github).

Pictured above are the features for a pooling layer from AlexNet trained on 40000+ retinal images using DIGITS 2(github). The feature images are displayed in false color and span the entire image.

Pictured above are the features for a pooling layer from AlexNet trained on 40000+ retinal images using DIGITS 2(github). The feature images are displayed in false color and span the entire image.

Reviewing the features in this layer indiciates they span the entire image and are primarily textural/vascular instead of point-like hemorrhages. When ophthalmologists described features indicating disease progression, the most difficult features to explain were the distributed textural features, usually corresponding to angiogenesis. Textural features are usually foreign to human perception because we do not encounter them in everyday experience – we are not trained on these features.

Physicians view automated diagnosis tools cautiously but welcome methods to improve their accuracy and standard of care. The right method will win out if it helps the physician. The most promising medical applications in DL are for “pre-screen” identification and visualizations tools. Going back to Robert’s quote, DL will help physicians train “smarter” by seeing more disease cases.

Further reading

Yann Lecun’s talk at GTC is a good introduction to DL (slides)

Andrej Karpathy’s blog out of Feifei Li’s lab covers recent topics in DL

Compressive sensing resources at Rice University (http://dsp.rice.edu/cs)